Lifting Up Carceral Narratives: Film, Archive and Advocacy

At IPMF, we are eager to support independent filmmakers from Greater Philadelphia who are telling stories that illuminate truths, challenge oppressive systems and inspire imagination and healing. The Local Filmmaker Fund just awarded 30 grants to filmmakers who explore the nuances and depth of human experience—from our bodies, to the borders we navigate and the movements that keep us safe.

And this past March, I had the opportunity to experience a collaboration between two local filmmaker grantees, Danie Harris and Lunise Cerin, who are exploring narratives of mass incarceration.

Lunise is currently teaching a media studies course called, “Prison Memory and Carceral Narratives" at Haverford College. She invited Danie Harris, resident filmmaker at Amistad Law Project and director of the short documentaries, “No Way Home" and “Care Team” (currently in post-production), to share her work and speak about her process, intentions, and advocacy efforts with students. Danie is one of a handful of guest speakers that Lunise has brought in this semester to help students reflect on their approach to storytelling, the responsibility they carry as media makers and the impact they hope to have.

What unfolded was a rich dialogue among the filmmakers and students, who are in the process of making short films that address mass incarceration. The course is part of the Graterford Archive Program, a digital archive developed and led by currently and formerly incarcerated partners in collaboration with Haverford College faculty and staff including Director Akeil Robertson, Project Manager Kali Silverman, and Archivist Wynn Eakins. The project will be activated through community practice, including oral history and storytelling workshops, installations, and art-making collaborations with justice-impacted families. The films that students produce are using material from that archive.

So much about this experience aligns with IPMF’s values and mission: the commitment to social justice storytelling, the collaboration among media makers, the preserving of memory from overlooked communities, and the intentional use of archives to create new stories, engage community and advocate for change.

Recently, I reached out to Danie and Lunise with some questions about their work. This conversation has been edited for brevity.

Nuala Cabral: Can you tell me what draws you to uplifting carceral narratives or stories about mass incarceration?

Lunise Cerin: First, thank you for the opportunity to talk about my class and the great work that the Graterford Archive is doing at Haverford College. I have worked as a documentary filmmaker for a little over 7 years, telling stories of Haitian resistance and liberation. In my work as a documentary editor and story producer, I have the privilege of centering and presenting narratives of oppressed people, people who have been harmed by media, misrepresented, and often not given the opportunity to tell their own truth on a global scale.

With that shared perspective and understanding of the urgency for new voices and practices in media, I was brought on as a facilitator for this class. So that’s what this class is: it’s a media studies and documentary workshop that invites our students to interrogate media’s impact on society and learn how to engage the medium in more thoughtful and human-centered ways. For me, it is an opportunity to stand in solidarity with folks also in the fight for black liberation here in Philadelphia.

Danie Harris: I was first drawn to telling carceral stories because there is so much storytelling work to be done in this field. "Tough-on-crime" narratives are deeply entrenched in our society, making carceral system reform feel nearly impossible, despite an abundance of evidence showing that alternative approaches yield better outcomes. Our focus needs to shift toward healing communities, rather than continuing to tear them apart unnecessarily—and storytelling is a critical tool in making that shift.

On a personal level, I’m drawn to telling these stories because of the relationships I’ve built through this work. The connections I’ve formed with individuals engaged in this movement have profoundly shaped my life, and I feel deeply passionate about continuing to support this work in any way I can. I also come from a conflict studies background, originally thinking I’d work in international conflict resolution. This same interest in how we understand each other across differences and repair harm that drew me to that work draws me to this field.

"My objective isn’t just “getting as many eyes as possible”—it’s about community building and shifting legislators' opinions. It’s specific, and specificity is where the magic happens"

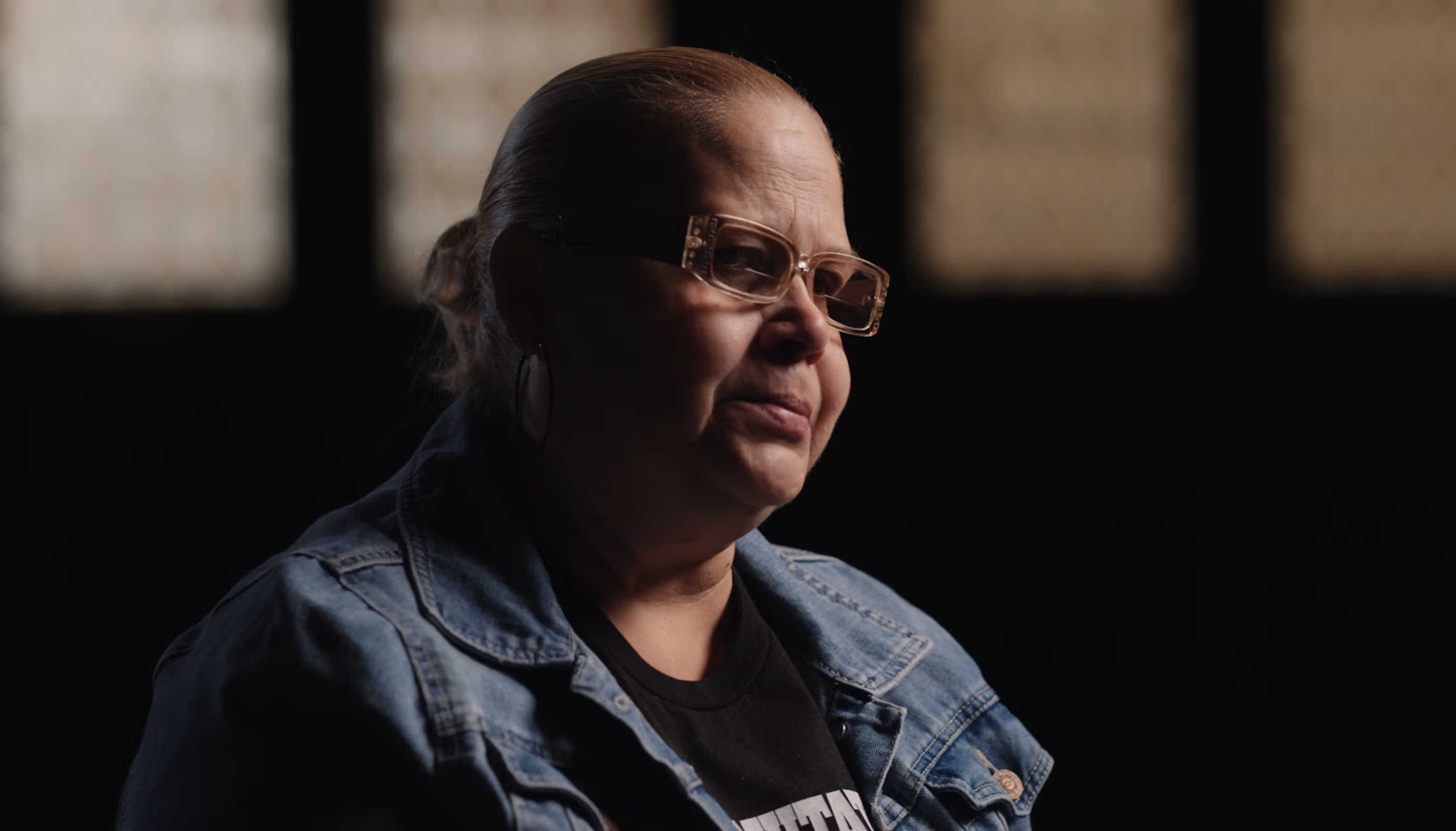

The cover photo of "No Way Home," directed by Danie Harris and produced by Amistad Law Project

Nuala: When telling stories about mass incarceration, what should filmmakers (particularly those who don't have experience with this carceral system) be mindful of? I'm curious if you could offer some examples or takeaways that have come up for you as a filmmaker, Danie, or for you Lunise, as a teacher who is guiding film students doing this work.

Lunise: To me, the number one thing is relationship and intention. You know, the importance of showing up with respect and curiosity, open to listening and learning before turning on any cameras or trying to address anything, cannot be overstated. Time and care are at the center of any ethical filmmaking practice.

Danie: First and foremost, I recommend to filmmakers who are new to any area of focus that you educate yourself. Be a fan and a student. As it relates to criminal justice systems, I think it’s helpful to understand how those who are working to tell stories about the system and needed change tell their stories. Watch films and read books that deepen your understanding of not just how the system operates, but the current reform work being done. This will enrich you as a person, a filmmaker and movement participant. Further after these things percolate, I find being a genuine student of what is out there helps me make better filmmaking decisions.

Some recommendations for self-education, especially if you have no direct experience with the system, include Locking Up Our Own, 13th, and The Sentence of Michael Thompson. Additionally, research organizations working on criminal justice reform and working with folks on the inside in your area. Read their blogs, listen to their podcasts, and immerse yourself.

Building relationships is also crucial, and deepening your own empathy and understanding of folks' experience will positively change how you make story decisions. I recommend attending meetups for groups like Coalition to Abolish Death By Incarceration (CADBI), grabbing coffee with organizers and those you meet, and immersing yourself in the community. It will change the way you approach your filmmaking and allow you to form deeper, more authentic relationships. Be curious, be open and acknowledge where you have gaps in your knowledge and lived experience. Let the people you meet guide you in where your story goes.

Nuala: Can you talk about what impact looks like for you as a filmmaker or educator, doing this work around carceral narratives? What is success?

Lunise: In a classroom setting, success has looked like our students beginning to question the media that they were raised to trust. It’s been a rewarding semester of discussing, studying, and realizing just how little we really know about the carceral system and how much misinformation is out there. Now, the students are currently in production for films of their own, and they are challenging the status quo and doing their part to illuminate biases and educate their peers. I find that incredibly inspiring.

Danie: My objective isn’t just “getting as many eyes as possible” — it’s about community building and shifting legislators' opinions. It’s specific, and specificity is where the magic happens. For me, I feel the most proud when I see the films I’ve made support community organizing. It’s impactful to me to see relationships are formed between community members or connections are reaffirmed between people who came together just to see the film. Impact, for me, is getting legislators in the room with community organizers—with the film serving as our “Trojan horse.” The film opens the conversation, touches hearts, and from there, the organizers and activists make change happen.

Nuala: I also asked Danie and Lunise if they had a question for each other and here’s what they shared…

Filmmakers: Danie Harris (left) and Lunise Cerin (right)

Lunise: What advice would you have for up-and-coming documentary filmmakers who are making advocacy pieces, especially in light of the current administration?

Danie: There's a Buddhist principle of the bodhisattva path that I've been thinking about in this work and during this time: engaging with suffering that is rooted in compassion and the deep interconnection of all of us. These are strange times to make films - especially documentaries in the advocacy space. However, it also feels like an important time to emphasize compassion and human interconnection even more urgently. My human compassion and my connection to myself and those around me - I think - has almost never been more important. And so as artists, as people, as makers of advocacy pieces, my number one piece of advice is to persist. Stay connected to that spark that makes you do this work. Protect that spark and clarity that drives you to these stories however you need to. Be in community as much as possible.

More tactical advice: the scale of productions we can pull off may change with different economic winds. I would encourage you to think through "the power of the possible" if that happens. Maybe you can't make the film exactly how you wanted to but can you tell a part of it with archival, cellphone video and different resources? Is there a TikTok version of this story that you can turn into something new and interesting for example?

Danie: How do you think this generation of students is bringing new perspectives to sharing carceral narratives and filmmaking? Do you notice different areas of passion, curiosity, or narrative approaches that feel fresh or different in this genre of filmmaking? Where do you think this genre of filmmaking will go?

Lunise: Working with this new generation of thinkers has been incredibly refreshing and inspiring. My class is composed mainly of Political Science and Psych majors who have a heart for social justice and hope to lead impactful lives. Because of the political realities of the last five years, college students are even more aware of our society's injustices than the generations before them. They're curious and questioning and want to contribute. It made for a really engaged class and some really great thoughtful discussions. With their films, I've really encouraged my students to lean into their artistic voices, and what has come of that is really exciting to witness. They all have incredibly unique voices and perspectives, so supporting them in bringing their visions to life is a pleasure and an honor.

*******

This moment is asking a lot of us right now. In the US, protest and dissent is becoming more and more criminalized. Vulnerable communities are losing benefits they need and people are being disappeared, illegally detained, and deported. Genocide continues to unfold with our tax dollars. Institutions that keep us safe are being slashed apart while prison profits and military budgets expand. Whether fascism is growing, or simply becoming more visible around us, many of us are feeling called to respond. As artists, as educators, as media makers, as funders, as human beings, many of us are wondering: where’s my lane?

Filmmakers Lunise and Danie have found a lane and here they offer a glimpse into what guides them. While their insight is useful to other filmmakers and educators, I’d argue their insight is valuable for funders who support the media and filmmaking landscape, as well. They are inviting funders of film and media to expand the way we think about impact and nuance our understanding of relationships, community care and responsibility. And they are inviting social justice funders, including those who resource decarceration, to recognize the power of narrative work, and the possibility of archive and memory.

The curiosity and hope Lunise observes and fosters in her students, and the urgency of compassion and human connection that motivates Danie to lift up carceral narratives, can inspire us to find our lane, and get clear about what it is that sustains us, what keeps us going.

So that when things feel overwhelming or impossible, that’s what we do: we keep going.

Feature photo credit: Sin Weng